Finding hard, crusty, almost rock-like patches on your dog's skin is alarming. It feels wrong. It looks wrong. If you're searching for answers, you've likely already heard the term calcinosis cutis. This isn't a primary disease but a striking symptom—a red flag waving from your dog's skin, signaling a deeper internal imbalance, most commonly too much cortisol in their system.

I've seen dozens of cases over the years, from the subtle early grit to the severe, plaque-ridden coats. The confusion and worry on an owner's face is universal. This guide cuts through that confusion. We'll walk through what it is, why it happens, how vets diagnose it, and the realistic path to treatment and recovery. Most importantly, we'll cover the home care details that make the difference between a slow, frustrating process and a smoother healing journey.

Quick Guide to This Article

What Exactly Is Calcinosis Cutis?

Let's break down the medical jargon. Calcinosis means calcium deposits. Cutis means skin. So, it's literally calcium deposited in the skin. Normally, calcium stays in bones and teeth. When a dog has certain metabolic disorders, calcium salts can precipitate out of the blood and lodge in the skin and underlying tissues. It's like limescale building up in a pipe, but it's happening in your dog's dermis.

The result isn't just a cosmetic issue. These deposits are foreign bodies. They irritate the surrounding tissue, often leading to intense inflammation, secondary bacterial infections, and ulcers. The skin can't breathe or function normally. It's uncomfortable, often itchy, and sometimes painful for the dog.

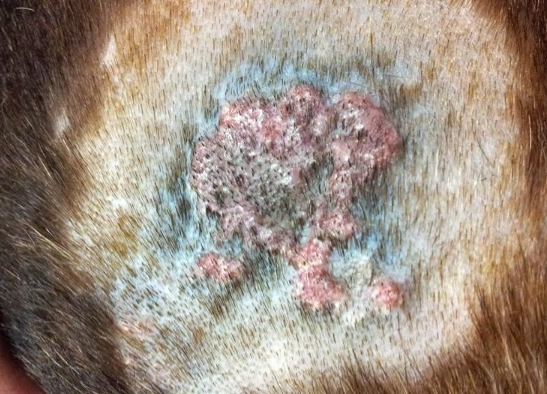

Spotting the Signs: From Grit to Plaques

The progression is usually gradual. In the early stages, you might feel something odd during a petting session.

- The Gritty Phase: Tiny, sand-like or gritty particles under the skin, especially along the spine, on the neck, in the armpits, or the groin. The hair might feel coarser.

- The Plaque Phase: The grit coalesces into firm, raised, white to yellowish plaques. They feel like pieces of chalk or hardened cement stuck to the skin. The surface is often rough and irregular.

- The Complicated Phase: Plaques become ulcerated, oozing, or infected. The skin around them is red, inflamed, and hairless. This is when dogs start licking, chewing, or scratching incessantly. A foul odor from secondary infection is common.

The Root Causes: It's Almost Never Just the Skin

This is the most critical part to understand. Treating the skin without addressing the cause is like mopping the floor with the tap still running. The vast majority of cases fall into one of these categories:

1. Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing's Disease)

This is the big one. It accounts for the majority of spontaneous cases. Cushing's disease means the adrenal glands produce too much cortisol, either from a tumor on the pituitary gland (most common) or on the adrenal gland itself. This excess cortisol disrupts calcium metabolism and collagen in the skin, creating the perfect environment for calcification. If your dog has calcinosis cutis, your vet will be highly suspicious of Cushing's. Other signs include increased thirst/urination, a pot-bellied appearance, and thinning skin.

2. Iatrogenic (Treatment-Induced)

"Iatrogenic" means caused by medical treatment. This happens when a dog is on long-term, high-dose corticosteroid medications (like prednisone) for allergies, immune diseases, or other conditions. The effect is the same as Cushing's—excess cortisol in the system—but the source is external. This is a tough spot for vets and owners, balancing the need for steroids against this severe side effect.

3. Other, Rarer Causes

These include chronic kidney disease, hypervitaminosis D (from certain rodenticides or supplements), and some connective tissue disorders. These are less common but will be investigated if Cushing's and iatrogenic causes are ruled out.

Getting a Diagnosis: What to Expect at the Vet

Don't be surprised if your vet visit feels comprehensive. They need to confirm the skin issue and hunt for the underlying cause.

- Physical Exam & History: They'll feel the lesions and ask detailed questions about your dog's health, thirst, appetite, and any medications.

- Skin Cytology & Biopsy: To confirm calcinosis cutis, they'll likely take samples. A fine needle aspirate can show calcium crystals under the microscope. A skin biopsy (a small punch sample sent to a lab) is the gold standard. It shows the calcium deposits within the skin layers definitively and rules out other rare conditions.

- Blood Work & Urinalysis: This is non-negotiable. A complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, and urinalysis look for signs of Cushing's (like elevated liver enzymes) and check kidney function.

- Diagnostic Testing for Cushing's: If Cushing's is suspected, your vet will recommend specific tests. The two main ones are the Low-Dose Dexamethasone Suppression (LDDS) Test and the ACTH Stimulation Test. These measure how your dog's adrenal glands respond to hormones and are crucial for pinpointing the type of Cushing's.

- Imaging: An abdominal ultrasound is common to visualize the adrenal glands and liver, and to look for tumors.

The process can feel lengthy and expensive, but it's necessary. Misdiagnosis leads to ineffective treatment and a suffering dog.

The Treatment Plan: A Two-Pronged Attack

Successful treatment always has two simultaneous goals: manage the skin lesions and correct the underlying cause.

Treating the Underlying Cause

| Cause | Primary Treatment Approach | What to Know |

|---|---|---|

| Cushing's Disease (Pituitary) | Daily oral medication: Trilostane (Vetoryl) is most common. It inhibits cortisol production. | Requires careful, ongoing monitoring with regular ACTH stimulation tests to adjust the dose. Lifelong treatment. |

| Cushing's Disease (Adrenal Tumor) | Surgical removal of the affected adrenal gland is often the treatment of choice. | Major surgery with risks, but can be curative. Requires a skilled surgeon and extensive pre-op workup. |

| Iatrogenic (Steroid-Induced) | Gradual, careful tapering of the steroid medication under vet supervision. | Never stop steroids abruptly. This can cause a life-threatening crisis. The taper must be slow, sometimes over months. |

Managing the Skin Lesions

While the root cause is being addressed, the plaques need direct care.

- Topical Therapies: Your vet may prescribe medicated shampoos (like antimicrobial or keratolytic shampoos) and topical treatments. DMSO gel is sometimes used as a carrier to help other medications penetrate or to help dissolve calcium. Important note: Do not use over-the-counter hydrocortisone creams. They can make the condition worse.

- Antibiotics & Anti-inflammatories: Secondary bacterial infections are almost a given. Oral antibiotics (based on culture and sensitivity) are often needed for weeks. Pain or itch relief may also be prescribed.

- Wound Care: For ulcerated plaques, gentle cleaning with saline or a prescribed antiseptic solution is key.

Home Care & Management: Your Day-to-Day Role

This is where you take the wheel. Recovery is slow, often taking 3 to 6 months after the cause is controlled for plaques to fully resolve. Your consistency matters.

The Daily/Weekly Routine

Gentle Cleaning: Use a soft cloth and the cleanser your vet recommends. Soak crusts gently to loosen them; never pick or pull at plaques, as this tears the fragile skin underneath.

Bathing Protocol: If medicated shampoos are prescribed, follow the instructions. Typically, you'll lather, let it sit on the skin for 5-10 minutes (contact time is critical), then rinse thoroughly. Pat dry, don't rub.

Applying Topicals: Wear gloves if using DMSO or other prescribed gels. Apply a thin layer only to the affected areas as directed.

Preventing Self-Trauma: An Elizabethan collar (cone) or a medical recovery suit is often essential to stop licking and chewing, which introduce bacteria and delay healing.

Supportive Measures

Diet: There's no magic diet for calcinosis cutis, but a high-quality, balanced diet supports overall skin health. Some vets recommend diets lower in calcium and vitamin D during active treatment, but this should be discussed with your vet—never make drastic dietary changes on your own.

Environment: Keep your dog's bedding clean and dry. Moisture can worsen skin infections.

Monitoring: Take weekly photos of the lesions from the same angle and distance. It's easy to forget how bad they were, and photos provide objective proof of slow improvement for you and your vet.

I remember a Dachshund named Bruno who had severe plaques. His owner was meticulous with the gentle cleaning and cone use, even though Bruno hated it. The plaques on his back took nearly 5 months to fully recede, but they did, and the hair even grew back in most spots. The owner's patience was the deciding factor.

Your Questions Answered

Finding reliable information online can be tough. For further reading on Cushing's disease, the American College of Veterinary Dermatology (ACVD) and resources like the Merck Veterinary Manual provide peer-reviewed, vet-level detail that can help you understand the diagnostic tests and medications your vet discusses.

Calcinosis cutis is a challenging condition, but it's manageable with a correct diagnosis, a committed veterinary team, and dedicated home care. The sight of those hard plaques softening and finally disappearing is one of the more rewarding experiences in managing chronic canine skin disease. Start with your vet, arm yourself with knowledge, and be prepared for a marathon, not a sprint.