Quick Guide

- The Male Cat Reproductive System: More Than Just the Obvious

- The Female Cat Reproductive System: A Complex Cycle of Readiness

- Side-by-Side: A Quick Comparison Table

- The Heat Cycle: What's Actually Happening?

- Mating, Pregnancy, and Birth: The Full Journey

- The #1 Thing Vets Wish You Knew: Spaying and Neutering

- Final Thoughts: Knowledge is Power (and Prevention)

Let's be honest, unless you're a breeder or a vet student, you probably haven't spent a lot of time thinking about the intricacies of the feline reproductive tract. Most of us cat owners just want to know the basics: why is my female cat yowling non-stop? What's with the male cat spraying my furniture? And is getting them "fixed" really that important?

I remember when I first got my cat, Mochi. She was a tiny ball of fluff, and the thought of her reproductive system was the furthest thing from my mind. That is, until she hit about six months old and the nightly operas began. That's when I had to dive deep, talk to vets, and really understand what was going on inside her. It's not just academic; understanding the male and female cat reproductive system is key to being a responsible pet owner, whether you plan to breed or, like most of us, you just want a happy, healthy companion.

So, we're going to break it all down. No overly complex jargon, no dry textbook descriptions. Just a clear, practical guide to what makes a tomcat a tomcat, a queen a queen, and everything that happens in between.

The Male Cat Reproductive System: More Than Just the Obvious

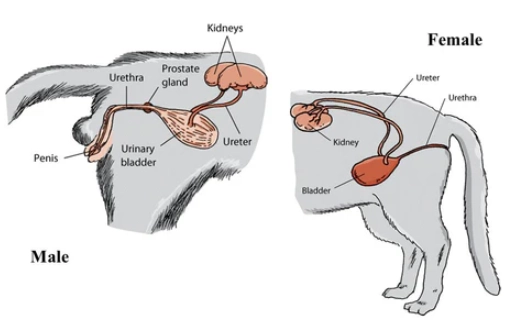

When people picture a male cat's anatomy, they usually think of the testicles. And while they're a major player, the system is a bit more sophisticated than that. It's a whole production line designed for one primary mission: to produce and deliver sperm.

The journey starts with the testes (or testicles). In kittens, these are tucked up inside the body near the kidneys. As the male kitten matures, usually by 2-3 months of age, they descend through the inguinal canal into the scrotum. That's right, male cats have a scrotum, it's just not very prominent and often hidden by fur. The testes have two jobs: produce sperm (in the seminiferous tubules) and produce testosterone (in the Leydig cells). Testosterone is the hormone behind all those classic "tomcat" behaviors—the territorial spraying, the aggression, the roaming, and that uniquely pungent urine odor.

Fun fact: A tomcat's barbed penis isn't just for show. It's believed the barbs stimulate ovulation in the female.

From the testes, sperm travel into the epididymis, a coiled tube where they mature and learn to swim. Think of it as a finishing school for sperm. When it's time for action, sperm are propelled into the vas deferens, the main transportation duct. This tube carries them up and around, eventually joining the urethra.

Now, the accessory sex glands are the unsung heroes here. The prostate gland and the bulbourethral glands add fluids to the sperm, creating semen. This fluid provides nutrients for the sperm and helps them survive the challenging journey into the female's reproductive tract. The whole package—sperm and fluid—then travels down the urethra, which runs through the penis.

The feline penis is unique. It points backwards (caudally) when not erect. And during erection, it doesn't just enlarge; it undergoes a specific muscular mechanism to point forward for mating. It's also covered in tiny, backward-pointing keratinized spines or barbs. These develop under the influence of testosterone and are a dead giveaway of a mature, intact male.

The Female Cat Reproductive System: A Complex Cycle of Readiness

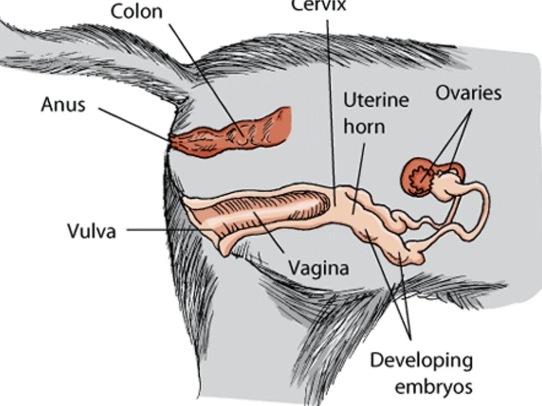

The female system, often called the queen's reproductive system, is all about cycles, receptivity, and potential for pregnancy. It's more internally complex than the male's.

The main event sites are the ovaries. These small, almond-shaped organs are located near the kidneys. They produce eggs (ova) and the key female hormones: estrogen and progesterone. Unlike humans who have a monthly cycle, cats are what we call "seasonally polyestrous." This means they go through multiple heat cycles during the breeding season (typically spring through fall, influenced by daylight length), and they ovulate only after mating. This is called induced ovulation.

When an egg is released from an ovary, it's caught by the funnel-like end of the oviduct (or Fallopian tube). This is the site of fertilization if sperm are present. The fertilized egg then travels to the uterus.

The feline uterus is described as bicornuate. Imagine a Y-shape. There's a short uterine body, which then splits into two long "horns" (the cornua). This design is perfect for housing multiple kittens in a single litter—they line up in each horn. The uterus is a muscular organ that nourishes the developing fetuses via placentas.

The lower part of the uterus is the cervix. It acts as a gatekeeper. It's usually tightly closed, preventing infection from entering. It only relaxes during estrus (heat) to allow sperm passage and, of course, during birth to let kittens out.

Everything leads to the vagina, which is the birth canal and the site where mating occurs. It leads to the external opening, the vulva. You might notice the vulva looking slightly swollen when a queen is in heat.

Side-by-Side: A Quick Comparison Table

Sometimes, seeing things side-by-side makes it click. Here’s a breakdown of the key components in the male and female cat reproductive system.

| Feature | Male Cat Reproductive System | Female Cat Reproductive System |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Organs | Testes, Epididymis, Vas Deferens, Penis | Ovaries, Oviducts, Uterus, Vagina |

| Key Hormone | Testosterone | Estrogen & Progesterone |

| Cycle Type | Continuous sperm production post-puberty | Seasonal Polyestrus (multiple heat cycles) |

| Ovulation | N/A | Induced (by mating) |

| External Signs | Barbed penis, small scrotum, jowly face (in some), spraying | Swollen vulva (subtle), vocalization, lordosis posture during heat |

| Primary Function | Produce & deliver sperm | Produce eggs, support pregnancy & birth |

| Common Health Risks (if intact) | Fight wounds, abscesses, testicular cancer | Pyometra, mammary cancer, ovarian cysts |

The Heat Cycle: What's Actually Happening?

This is where theory meets the very noisy, very annoying reality for many owners. The queen's heat cycle has four stages, but we really only notice one.

- Proestrus: This lasts just a day or two. You might not even notice. Hormone levels are shifting, and she may be slightly more affectionate but will reject any male advances.

- Estrus ("Heat"): Bingo. This is the stage. Lasting 4-7 days on average (but can be longer!), this is when she is receptive to mating. Estrogen peaks. Her behavior screams "I'm ready!" – loud, persistent crying (caterwauling), rolling on the floor, raising her hindquarters in the air (lordosis posture), and being excessively affectionate. She may also spray urine or try to escape outdoors. If she mates and ovulates, she moves on. If not, she goes to...

- Interestrus: The break. If she didn't ovulate, she'll have a quiet period of 1-2 weeks before cycling back into proestrus and estrus again. This can repeat all season long. Exhausting, right?

- Diestrus/Pregnancy: If she ovulates (from mating), she enters diestrus. Her body acts as if it's pregnant, thanks to progesterone. If she was actually fertilized, this is the 63-65 day gestation period. If she wasn't fertilized, she may have a "false pregnancy" for about 40-50 days before returning to interestrus.

- Anestrus: The off-season. During shorter daylight periods (winter), she may take a complete break from cycling.

I can still hear Mochi's heat cries in my dreams. It was relentless.

Mating, Pregnancy, and Birth: The Full Journey

So how do these two systems come together? It's a brief, often violent-looking affair. The male mounts the receptive female, grips her neck scruff, and copulation is quick. The female usually screams and may turn to swat at the male afterwards—this is a reaction to the barbed penis stimulating ovulation.

That stimulation triggers a hormonal cascade from her brain, leading to ovulation within 24-48 hours. Sperm can survive in her tract for several days, waiting for the eggs. Fertilization happens in the oviducts.

Pregnancy Timeline

- Weeks 1-3: Embryos travel to the uterus and implant. Little visible change.

- Week 4: A vet can often confirm pregnancy via ultrasound. Her appetite increases. Nipples may become pinker and more prominent ("pinking up").

- Weeks 5-6: Weight gain and abdominal swelling become obvious. She may start nesting behavior.

- Weeks 7-9: You might feel kittens moving! She'll seek out quiet, safe places. Milk production may start a few days before birth.

Birth (queening) is usually straightforward. It happens in three stages: restlessness and nesting (stage 1), active delivery of kittens (stage 2), and passing of the placentas (stage 3). The whole process can take several hours.

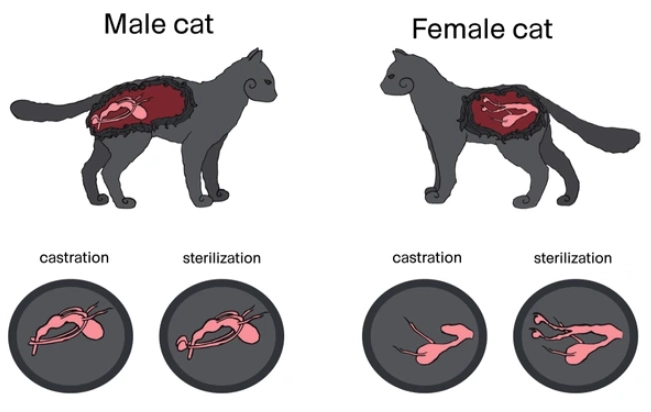

The #1 Thing Vets Wish You Knew: Spaying and Neutering

We have to talk about this. It's the single most important action you take regarding your cat's reproductive health. It's not just about population control; it's about preventing serious diseases and awful behaviors.

Spaying (Ovariohysterectomy): The surgical removal of a female cat's ovaries and uterus. This eliminates heat cycles, prevents pregnancy, and, crucially, prevents pyometra and dramatically reduces the risk of mammary cancer (if done before the first heat). Organizations like the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) provide extensive resources on the benefits of this procedure.

Neutering/Castration: The surgical removal of a male cat's testes. This stops sperm and testosterone production. Results? No more spraying (in ~90% of cats), reduced aggression and roaming, loss of those pungent urine odors, and elimination of testicular cancer risk. The Cornell Feline Health Center is a fantastic, authoritative source for details on feline surgical care and its long-term benefits.

Your Burning Questions, Answered

Let's tackle some of the specific questions that pop up when people are researching the cat reproductive system male and female.

At what age do cats become sexually mature?

This can be surprisingly early. Females can go into their first heat as young as 4 months old, though 5-6 months is more typical. Males become capable of fathering kittens around 6-8 months, but they might start practicing mounting behaviors earlier. This is why the standard recommendation is to spay/neuter around 4-6 months, before sexual maturity hits.

How can I tell if my cat is in heat vs. sick?

Great question. A cat in heat is usually VERY vocal but otherwise acts normally—she'll eat, drink, and play. She'll present the lordosis posture. A sick cat might be lethargic, hide, have a reduced appetite, or have other symptoms like vomiting/diarrhea. The yowling of heat is distinct: it's loud, drawn-out, and sounds like distress but isn't. When in doubt, call your vet.

Can a litter of kittens have different fathers?

Absolutely. A queen can mate with multiple tomcats during a single heat cycle. She releases multiple eggs, and each can be fertilized by sperm from a different male. This is called superfecundation. So yes, that litter of multicolored kittens might literally have different dads.

What is pyometra and why is it so dangerous?

Pyometra is a bacterial infection of the uterus that occurs in older, unspayed females, often a few weeks after a heat cycle. The hormone-progesterone thickens the uterine lining, and bacteria can ascend from the vagina. The cervix is closed, so the pus has nowhere to go. The uterus fills with toxic pus, leading to sepsis and death if not treated urgently. Treatment is an emergency spay. It's a stark, scary example of why leaving a female intact "just because" is a major health gamble.

Is there such a thing as cat menopause?

No. Unlike humans, female cats do not go through a menopause where they permanently stop cycling. They can continue to go into heat cycles seasonally for their entire lives, though fertility does decline with age. An elderly intact female cat is still at risk for pyometra and other reproductive issues.

Final Thoughts: Knowledge is Power (and Prevention)

Peeking inside the world of the cat reproductive system, both male and female, gives you a huge advantage as an owner. You stop seeing behaviors like spraying or yowling as mere nuisances and start understanding them as symptoms of a deep-seated biological drive.

You also become equipped to make the best health decisions. Knowing that a simple, routine surgery can virtually eliminate the risk of deadly cancers and infections like pyometra changes the calculus completely. For reputable, in-depth medical guidelines on these procedures, the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) sets the standards that most vets follow.

Whether you're a curious new owner, someone dealing with a cat in heat for the first time, or considering breeding (please do your research ethically!), understanding this fundamental aspect of feline biology is key. It allows you to work with their nature, not against it, and provides the foundation for a long, healthy, and happy life together. After all, we want our cats to be cherished family members, not governed by instincts that cause them—and us—stress.

And trust me, your furniture will thank you for getting rid of the spray.